: Riding the winds of change: Singapore companies seize offshore wind opportunities in the UK

[ABERDEEN, UK] Singapore’s busy waters may be unsuitable for offshore wind turbines, but the Republic’s marine capabilities are going far in the United Kingdom – the world’s second-largest offshore wind market, and Europe’s largest.

With many existing and upcoming offshore wind farms, the UK is an ideal place to join the ecosystem, industry players told The Business Times in interviews in London and across Scotland.

The UK aims to achieve up to 50 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind by 2030, with 5 GW from floating farms, notes Enterprise Singapore (EnterpriseSG) director for Europe Alan Yeo.

The European country currently has an installed capacity of some 14 GW, “so there are still many opportunities for our companies to tap on”, he adds.

Scottish cities such as Aberdeen and Montrose, near the North Sea, were traditional oil and gas centres. But as the world moves away from fossil fuels, many in these cities – including Singapore companies setting up there – are ready to reinvent the UK as an offshore wind hub.

Says Yeo: “Despite a lack of domestic wind energy market, Singapore can leverage existing capabilities in marine and offshore energy (M&OE) to support global offshore wind projects.”

There are crossover chances for the Republic’s oil and gas players in particular, he adds, as the scale of their infrastructure and assets, as well as operating conditions, are similar to those of offshore wind farms.

These M&OE companies could adapt to take part in constructing critical components in the wind energy value chain, such as offshore substations, support vessels and mooring products.

Building blocks

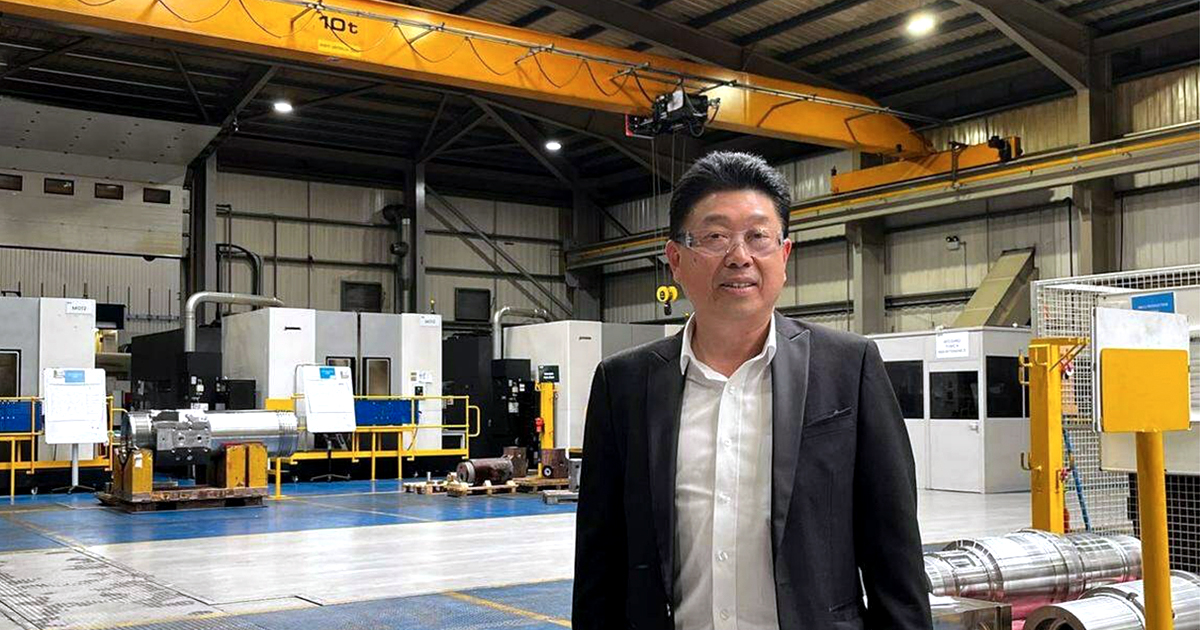

One basic requirement for offshore wind farms is, of course, wind turbines. Singapore-based AME International has entered the value chain at an early point by manufacturing turbine parts.

The turnkey manufacturer mainly makes components for industries such as oil and gas, and has clients around the world, including in the UK.

Even as it enters offshore wind, oil and gas remains its “bread and butter” for now, says chairman and managing director Steven Toy.

Instead of converting current facilities – “I have my commitment to my oil and gas customers”, says Toy – the company is expanding to serve offshore wind clients.

In late 2023, AME entered Montrose by acquiring an 8,000 square metre subsea equipment machining facility from oil and gas giant Baker Hughes, close to offshore wind projects. It is now buying neighbouring land so it can increase its manufacturing capacity.

Toy intends to commit up to US$20 million to purchase the 1.5 hectare plot and new equipment.

“The closest to offshore wind, in this (engineering and manufacturing space), is oil and gas,” he says. The industries use components of similar size, weight and material, such as alloy steel that can withstand high pressures. “It’s still out at sea, with that kind of very harsh environment.”

Offshore wind turbines comprise numerous precision metal components, and AME hopes to use its capabilities and machines in this area to make offshore wind parts, such as nacelles – protective structures that house key components – and gearboxes, which boost the speed of turbines.

While it is still developing capabilities, the company hopes to secure its first offshore wind customer by next year.

Offshore wind is not yet highly profitable, as it produces energy at a higher cost but has to keep its selling prices aligned with those of oil and gas power to appeal to consumers, says Toy.

But ideally, the sector will eventually contribute 20 to 30 per cent of the company’s revenue, he adds.

Plugging in the pieces

Once made, turbines need to be anchored. Catalist-listed Mooreast Holdings specialises in designing, engineering, supplying and procuring such mooring solutions, having begun in offshore oil and gas before entering offshore wind.

Floating wind farms are less common than fixed wind farms, as they cost more and their technology is less developed. But they are expected to grow more popular, as they can be positioned further offshore and thus generate more energy.

The base theory in oil and gas and floating offshore wind is the same, says executive director Sim Koon Lam.

In February 2023, Mooreast signed a collaboration agreement with ETZ – a private sector-led, not-for-profit company spearheading North-east Scotland’s energy transition – to set up a facility in Aberdeen to produce mooring components. This will be in addition to Mooreast’s existing production capacity in Singapore.

The facility will be built on a seven to 10-hectare site close to Aberdeen’s South Harbour, and is likely to be completed by 2027.

Aberdeen’s location close to offshore wind developments makes it a good choice, considering the logistical difficulty of transporting large equipment, says Sim. As a hotbed for offshore activity, it also has a strong ecosystem of talent and supporting industries.

Its location also allows Mooreast to tap the pipeline of offshore wind projects in leasing rounds launched by government agency Crown Estate Scotland.

Developers awarded projects under the agency’s Innovation and Targeted Oil & Gas (INTOG) and ScotWind leasing rounds have committed to capital expenditure within Scotland and the UK, notes Mooreast UK & Ireland business development manager Jack Phillips.

It is thus crucial for industry players to have representation in the UK market, and Scotland specifically, he says.

For ScotWind, for example, developers are expected to spend £28.8 billion (S$50 billion) across 20 projects, or an average of a £1.4 billion investment in Scotland per project built.

Though it will take several years for Mooreast to begin production in the country, its commitment there has allowed it to engage potential buyers. Phillips says: “At the moment, there is no manufacturing capacity here within Scotland as well, for our range of products.”

The company is in the conceptualisation and pre-engineering stage for various projects, and hopes to start constructing and procuring parts for INTOG projects from 2025 to 2027, and ScotWind projects from 2027 to beyond the decade.

“These projects will run for six, eight, 10, 20 years,” says Barry Silver, Mooreast UK and Ireland managing director. “So from a business perspective, you have long-term, long-standing contracts that are quite attractive rather than short, sharp, punchy contracts. You actually have longevity in your business planning as well.”

With a planned expansion in Singapore, Mooreast will be able to produce and export enough subsea foundations there to support 1.5 to 2 GW of floating offshore wind energy per annum – a small fraction of the global addressable market.

Sim aims to achieve half this capacity in the Aberdeen facility, which he believes will take at least three to five years to scale up.

Beyond the UK, continental Europe is also a promising export market. Some 165 GW of wind farm capacity is in the pipeline, which will require 65,340 mooring systems.

Given the huge demand, the Scottish operations will not be able to serve the entire region, says Sim. In Rotterdam, Mooreast’s third location, the company will likely continue to operate through a third-party manufacturer.

But he adds: “Maybe in the near future, there will be a plant out from Rotterdam.”

Ships out at sea

For offshore wind farms to be built, components and equipment must be brought out to sea and maintained there. This is where offshore wind vessels – and Singapore-headquartered Cyan Renewables – come into play.

Such vessels might be used for ecological studies; installing “air curtains” to protect marine life; installing turbines; piling and cable-laying; and transporting parts for maintenance.

A portfolio company of infrastructure fund Seraya Partners, Cyan intends to invest US$1 billion in the next three years on specialised vessels for the offshore wind industry.

This includes building up local teams and investing, owning and operating offshore wind vessels. It has identified Europe, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Australia as key markets, and recently acquired Australian offshore vessel provider MMA Offshore for A$1.1 billion (S$970 million).

Group chief executive officer Lee Keng Lin sees robust demand for new vessels because offshore wind turbines are of a comparable height to the Eiffel Tower, and keep getting bigger as capacity increases.

Many vessels built a decade ago are now too small, he adds. “That explains why there’s a shortage and demand for more vessels going forward.”

Cyan is well-placed to address this shortage, says Lee. Members of its management have long working relationships with global shipyards; the company has a fleet of vessels that are suitable for offshore wind; it has specialist knowledge of vessels and the different regulations of various markets; and it has the know-how to train manpower for the industry.

“We want to establish our track record in Europe, because that’s where most of the international developers are based,” says Lee.

This January, Cyan entered the UK with its purchase of Aberdeen-founded Sentinel Marine, whose 14 offshore support vessels were chiefly used for emergency response and rescue. Working with Cyan, Sentinel Marine now hopes to explore opportunities in offshore wind with both new clients and existing ones looking to transition away from oil and gas.

Its vessels do not need to be modified to serve wind farms, as they are already equipped for geophysical studies, installing bubble curtains, and serving as “floating hotels” for offshore technicians.

If anything, Sentinel Marine lacks supply, as its vessels are tied up with long-term charters. It thus aims to double its fleet in the next five years or so through acquisitions and new builds, with Cyan’s support.

Sending back to shore

After turbines are set up and spinning, the power generated needs to be processed, enabled by players such as Temasek-owned Seatrium.

In offshore wind, the company has previously designed and constructed installation vessels for its clients, and delivered fixed-platform substations. The Seatrium Offshore Renewable Services (ORS) unit in the UK supports its end-to-end delivery of such projects in Europe.

For instance, after the installation of a fixed-platform substation for electricity transmission system operator Tennet – which operates in the Netherlands and Germany – Seatrium ORS carried out tests and approved the systems to ensure it was ready for operations.

Substations are the intermediary platforms between wind turbines and grid connections. They collect power generated by wind turbines turning at different speeds, “even out” the electricity generated, and transmit it to shore via subsea cables, explains Seatrium ORS managing director Colin Yaxley. The “cleaned” power is further converted onshore and exported to the grid.

Beyond the launch of projects, Seatrium ORS also provides integrated maintenance services.

Seatrium’s order book includes 8.3 GW of offshore wind fixed-platform solutions for the European market, contributing to Europe’s goal of achieving over 100 GW of offshore wind power by 2030, and up to 450 GW by 2050.

Based on its 2023 financial year results, about 39 per cent of its net order book consisted of projects related to renewables and cleaner or green solutions, primarily in offshore wind. Generally, most of such offshore wind projects are for wind farms in the UK and Europe.

This is close to Seatrium’s target of 40 per cent by 2030, though the figure may fluctuate annually based on contracts secured. While more fixed offshore-wind projects are in the pipeline, the company is also developing floating wind turbine foundations and substation platforms, to tap the growing market.

To take advantage of the burgeoning offshore wind industry, EnterpriseSG has been working to identify opportunities for supply chain and co-innovation collaborations with Singapore companies.

In the UK, this includes engaging government authorities and industry partners, as well as sharing market developments with Singapore companies and connecting them to business opportunities.

In June this year, the agency brought a delegation of nine companies across the offshore wind value chain to the Global Offshore Wind trade show in Manchester, for meetings and networking. It also arranged meetings with other industry partners in the UK.

“These platforms help to expose our companies to relevant opportunities, facilitate introductions to global developers, and showcase that Singapore companies possess the requisite capabilities to be plugged into their supply chain,” says EnterpriseSG’s Yeo.